1

REVIEW

of the

Sea Turtle Science and Recovery Program

Padre Island National Seashore

Recommended: Patrick Malone, Regional Chief, Natural Resources

Reviewed and concurred: Jennifer Carpenter, Associate Regional Director,

Resource Stewardship and Science

Signed:_____ ______approved 6/8/2020; amended 5/7/2021

Michael T. Reynolds

Regional Director, NPS Regional Office serving DOI Regions 6,7,8

2

Top: Kemp’s ridley in water; Lower left: Female Kemp’s laying eggs; Lower right: Kemp’s hatchlings at

release (NPS photos)

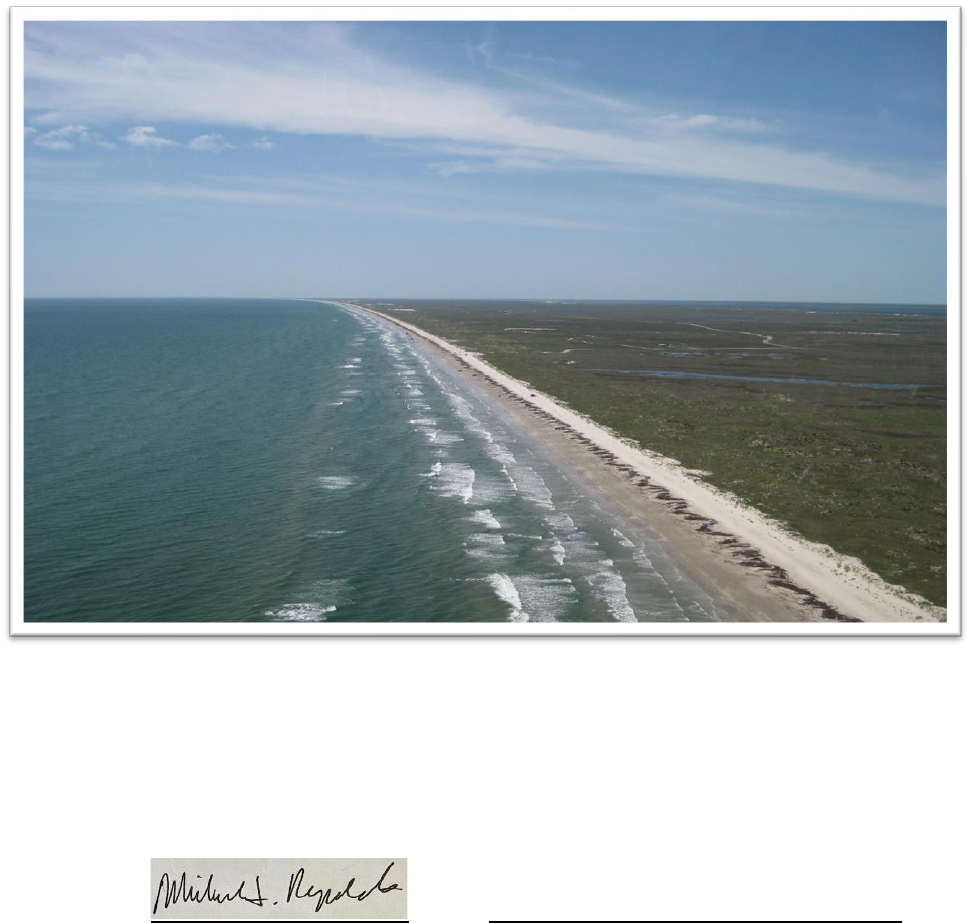

Cover photo: Shoreline of the barrier island known as North Padre Island, home of Padre Island National

Seashore. (NPS photo)

Editor’s Note: The report was first approved on 6/8/20. Requests for information correction under the

Information Quality Act were received on 7/16/20 and 12/31/20. Minor information corrections were

completed, along with footnotes and appendices added to provide clarifying information, on 12/2/20 and

5/7/21. A record of these actions can be found at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/information-quality-

corrections.htm.

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS or park) Sea Turtle Science and Recovery (STSR)

program has been operating for over 40 years. Begun in the late 1970s to aid in the recovery of

the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, the most endangered sea turtle in the U.S., a secondary nesting

colony was successfully established at PAIS to prevent species extinction. The park has been

relocating sea turtle eggs, incubating them in an NPS facility, and releasing hatchlings on park

beaches to mitigate potential effects from any source of environmental, natural, or human

caused mortality ranging from tidal inundation, predation, and recreational beach driving. The

program has grown tremendously during this time and now has an annual operating budget of

nearly $2M ($1.3 ONPS base and $700k project funds), which funds nest monitoring and

management, research, and stranding response. In 3-5 years, the program is projecting a

budget shortfall. A program review was requested to evaluate the financial sustainability of the

program, including reviewing program operations, staffing, interagency relationships, and

consistency with conservation principles and agency policy.

From 1978 to present, the worldwide population of Kemp’s has grown, but is still tenuous. The

epicenter for Kemp’s nesting is in Mexico. Kemp’s ridley nesting in Texas and at PAIS

represents about 1% of the worldwide total. Nationally and internationally, those agencies with

authority over species recovery have emphasized reducing threats and impacts to the species,

including focusing recovery efforts on primary nesting areas in Mexico and reducing egg

harvesting and bycatch in fishing gear (mostly shrimp trawling). The STSR program has

contributed significantly to sea turtle science over the years through research and dozens of

professional publications. The park’s sea turtle nest protection/relocation/egg incubation

program can be credited for improving the science and techniques for hatchling production.

However, the program does implement very intensive and invasive techniques to reduce

potential egg and hatchling mortality on only one percent of the worldwide population. Other

influences, such as sea level rise and increases in coastal nuisance flooding, contribute to the

concern over the long-term suitability and availability of sea turtle nesting habitat at PAIS and

indicate a need to determine if other suitable nesting habitat exists along U.S. beaches outside

of PAIS.

Program findings and recommendations are included on the topics of mission and program

focus, interagency relations, sustainable funding, program staffing and operations, and safety.

This report includes many recommendations intended to update the program to better align with

current NPS practices, which includes continuing to contribute to sea turtle recovery and

protecting and managing the many other significant natural and cultural resources in the park.

The park has achieved establishment of a secondary nesting colony of Kemp’s and evidence

indicates the imprinting and return of offspring to PAIS beaches. This strategy was a key

component of the 1978 interagency Kemp’s action plan, but has not been identified as a primary

recovery action in subsequent FWS/NMFS recovery plans, including the most recent 2011 plan.

The park has an opportunity to scale STSR program operations and to pilot alternate nest

management strategies, which will require engaging other agencies and partners in planning for

4

the future, including Endangered Species Act consultation. The 5-year species status review for

Kemp’s (to be conducted in 2020) will be an opportunity to initiate these discussions with the

Recovery Team and other partners.

Sea turtle management of Kemp’s ridley requires international and domestic coordination and

partnerships that promote shared stewardship. The STSR was universally praised for raising

public awareness for sea turtle conservation. NPS funding, particularly PAIS funding, for

Kemp’s recovery is disproportionately high compared to the number of partners involved and

the percentage of the turtle population being addressed. The NPS should request additional

funding and support from the FWS for current recovery actions and nest location, egg collection,

and hatchling release at PAIS. The NMFS currently supports PAIS for the role of State

Coordinator of the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network for Texas. The park should

engage the national Kemp’s Recovery Team and the FWS in determining and evaluating

additional and alternative locations for nesting sites outside of PAIS boundaries.

For a sustainable program operations funding model, the park should transition the sea turtle

program to one that operates on existing park base that accounts for and incorporates existing

permanent salaries and other fixed costs (e.g. fuel use, supplies, equipment, all vehicle

maintenance and replacement, and additional utility costs). The program should not rely on

additional parkwide base fund allocations or short-term project funding to cover long-term

operational costs.

Alternative staffing and operations recommendations include greatly reducing overtime from

over $200,000 per year to approximately $16,000 per year (the NPS Scorecard standard for

resource programs), elimination of administratively uncontrollable overtime (AUO), and hiring

additional seasonal staff to accomplish priority work. A reorganization of the staffing structure is

proposed to reduce supervisory span of control issues and provide for more direct interaction of

permanent staff with the division chief. Additional operational recommendations include

focusing staff work and activities (e.g. nest management and egg collection, turtle stranding,

recovery, and salvage) to within PAIS boundaries. To reduce employee burnout and provide for

adequate work-rest ratios for normal operations, tours of duty should be limited to 8-hour days

or 10-hour days (40 hours per week) and additional seasonal staff should be hired for days or

times where coverage is demonstrated as critical.

The Regional Safety Officer recently completed a safety review in December 2019, which

included a corrective action plan for beach travel. A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)

should be developed defining when the beach is closed to the public, and STSR staff should be

held to that standard. The park should implement an incident command system (ICS) for

management of large and unpredictable turtle stranding events to improve accountability for

tasks, safety, and finances. Operational Leadership (OL) training should be provided each year

to all staff and OL principles and activities (e.g. GARs) should be conducted regularly to

evaluate conditions and risks unfavorable for field work and any mitigations needed.

5

Table of Contents

1. Program Review Purpose, Scope, and Objectives……………………………………………7

2. Assessment Methods…………………………………………………………………………….7

3. Program History and Context……………………………………………………………………7

4. Findings, Discussion, and Recommendations

a. Mission Functions……………………………………………………………………...10

i. Nest Management…………………………………………………………….11

ii. Strandings……………………………………………………………………..17

iii. Research……………………………………………………………………….19

b. Funding…………………………………………………………………………………20

c. Staffing………………………………………………………………………………….29

d. Safety……………………………………………………………………………………31

e. Interagency Relationships…………………………………………………………….33

5. Program Successes……………………………………………………………………………..36

6. References……………………………………………………………………………………….37

7. Report Preparers and Reviewers………………………………………………………………38

8. List of Agencies, Organizations, and Individuals Interviewed………………………………38

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1. Map of Padre Island National Seashore…………………………………………………....6

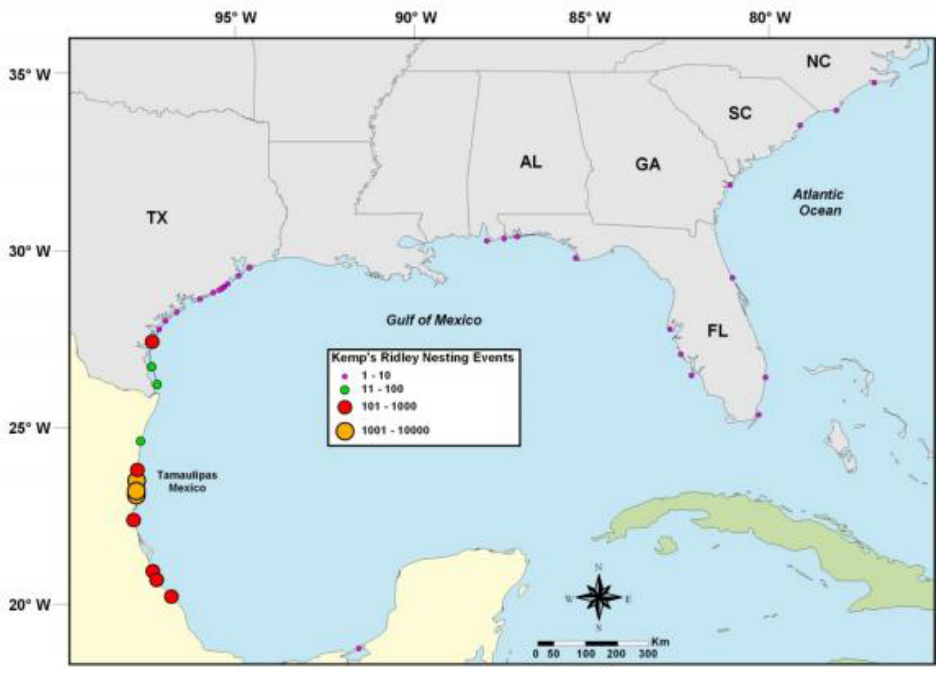

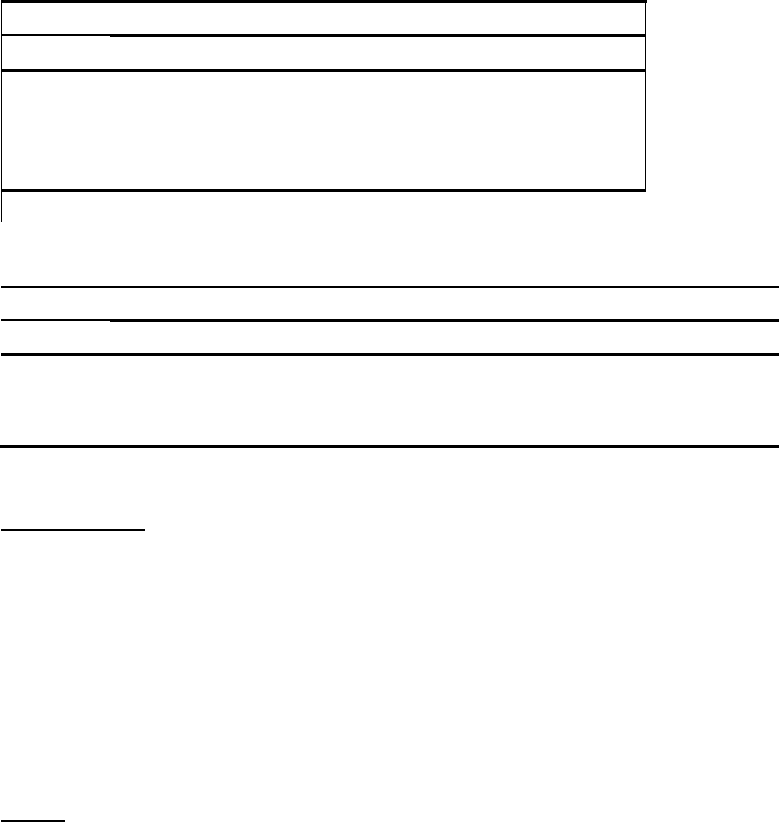

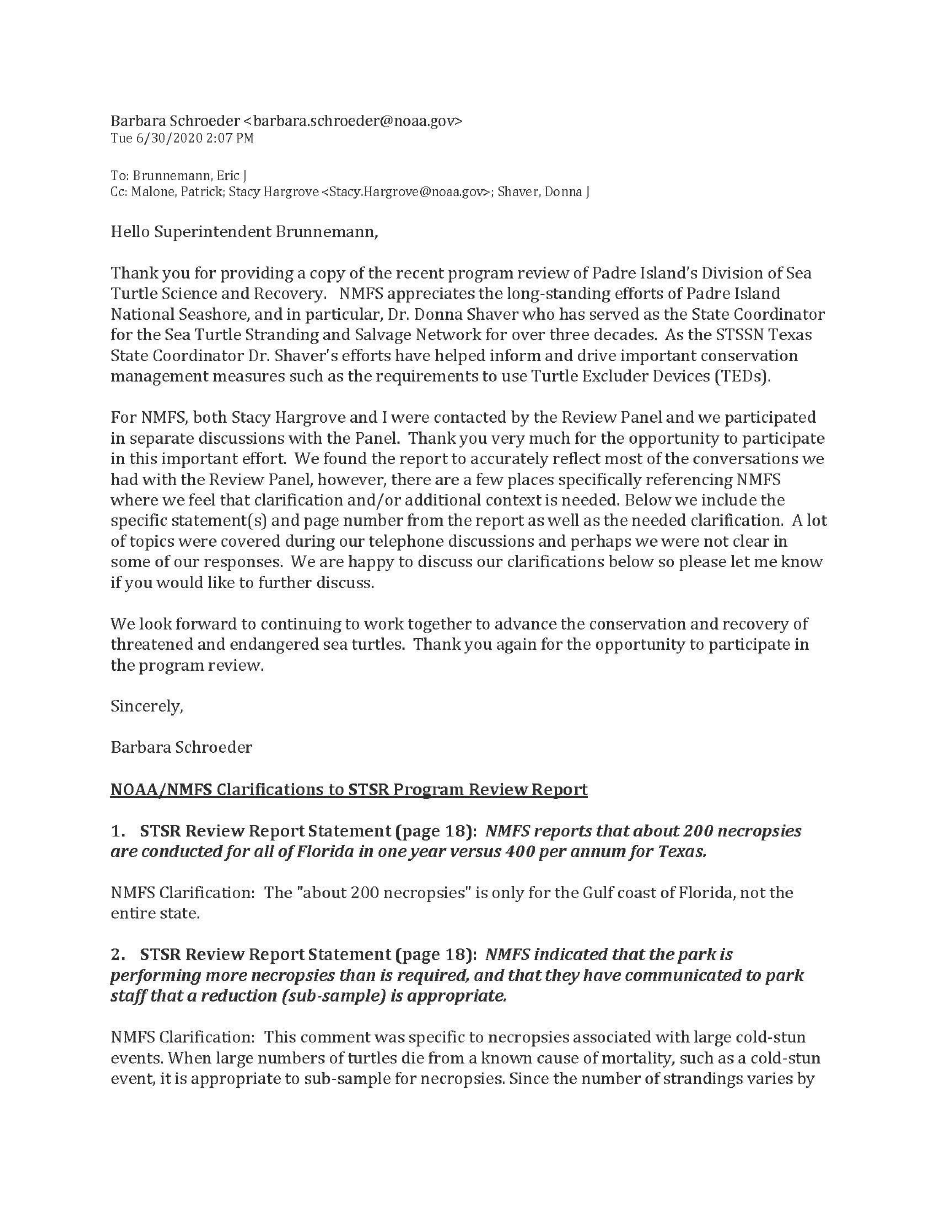

Figure 2. Distribution and relative abundance of Kemp’s ridley nesting……………………………9

Table 1. Kemp’s ridley sea turtle nests……………………………………………………………….43

Table 2. Green sea turtle nests for select areas of North Atlantic Population……………………43

List of Appendices

Appendix A: Park Purpose, Significance, Fundamental Resources and Values…………………40

Appendix B: Nests Detected of Kemp’s ridley and Green Sea Turtles&ESA Recovery Criteria.43

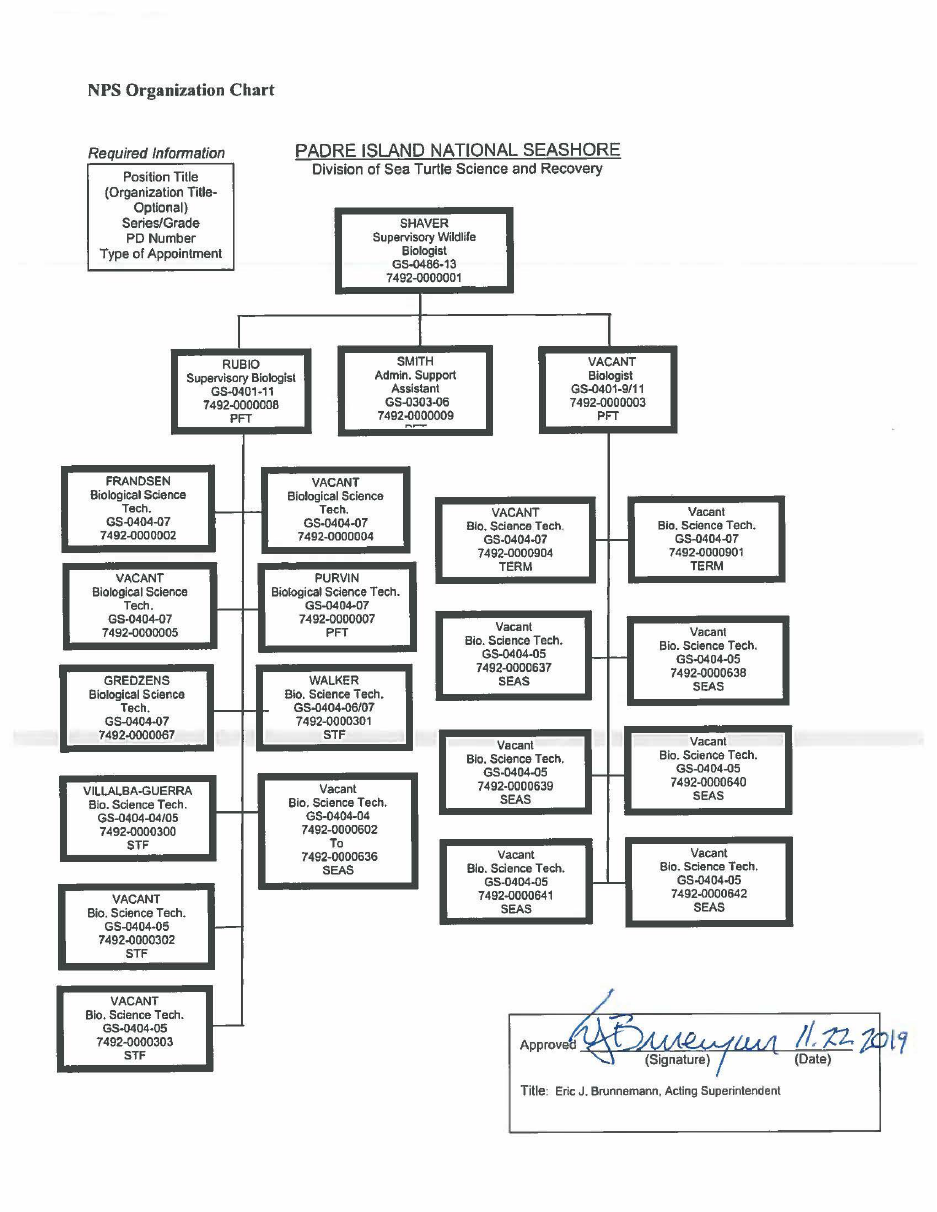

Appendix C: PAIS STSR Organizational Chart (FY20)……………………………………………..44

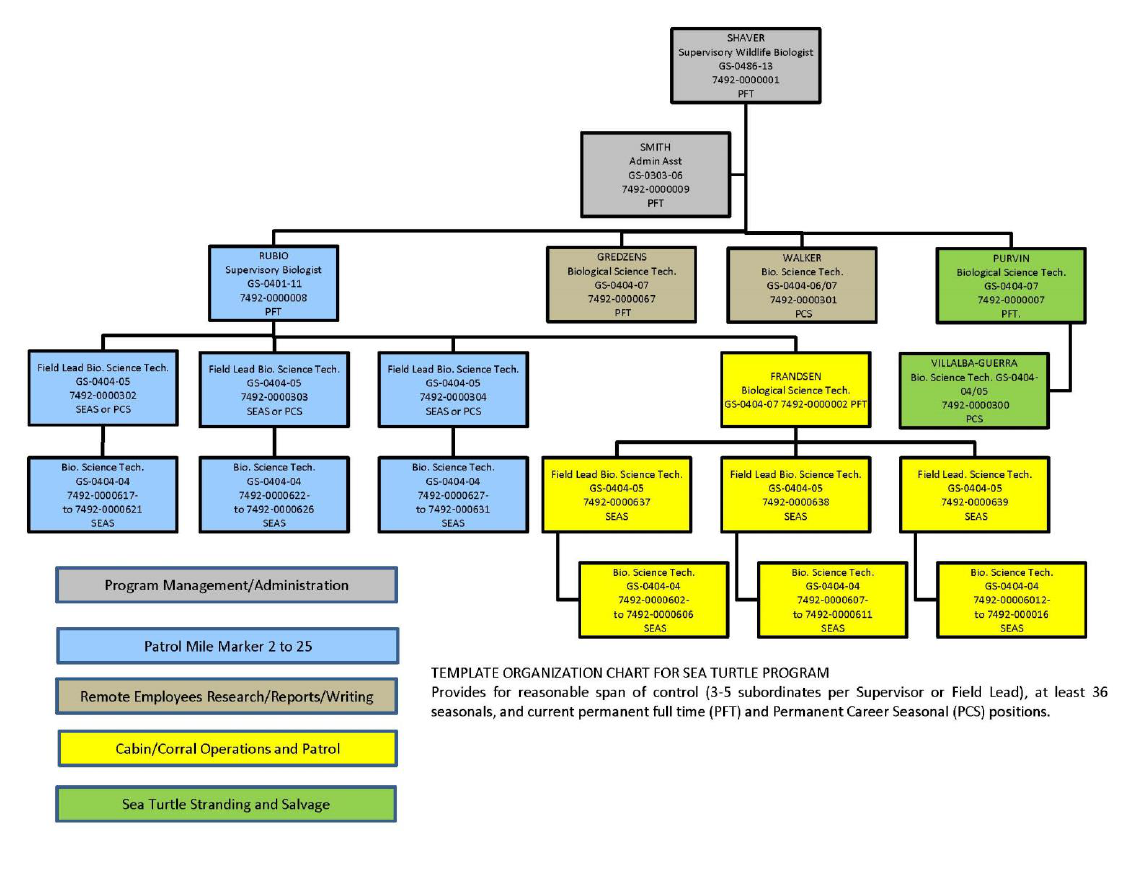

Appendix D: PAIS STSR Organizational Chart (recommended)………………………………..…45

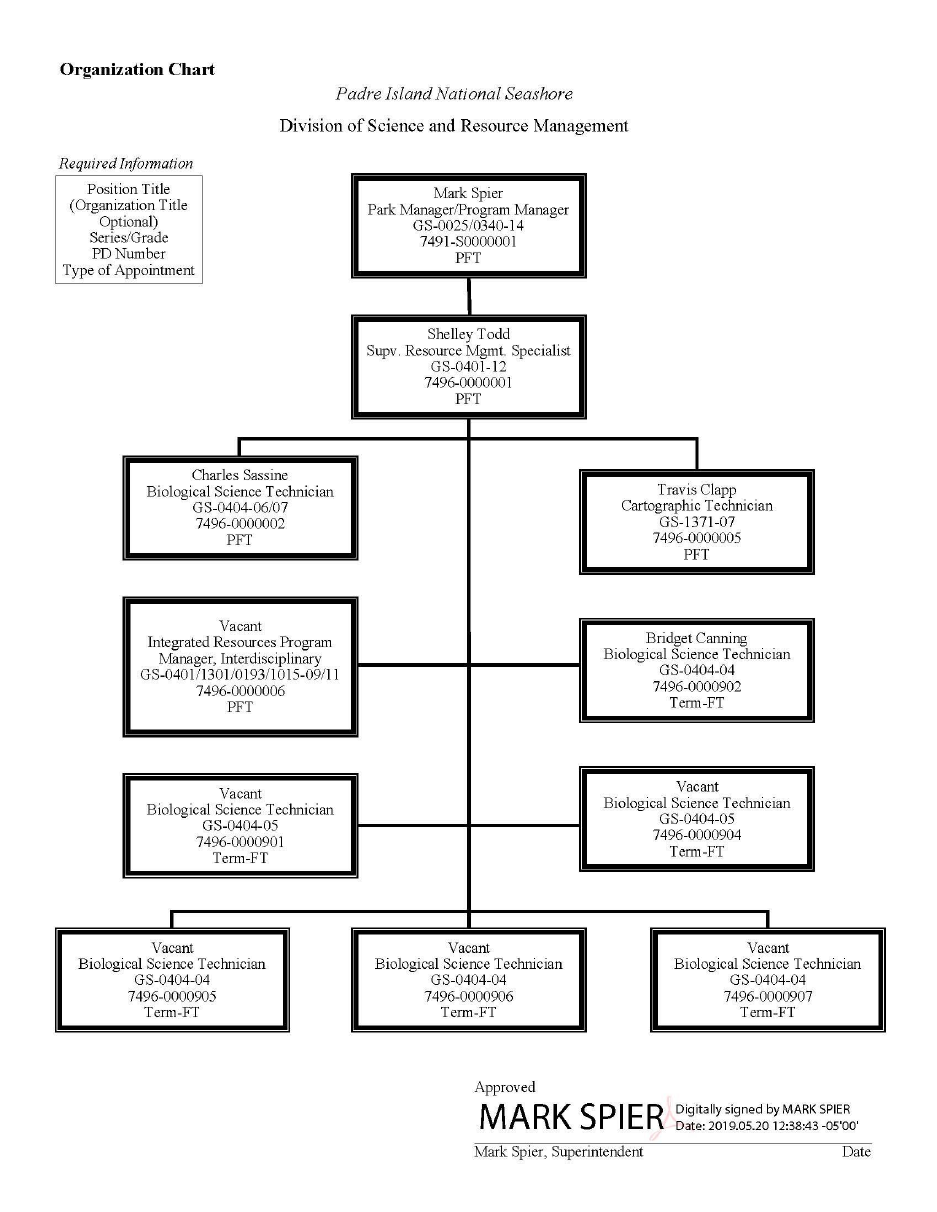

Appendix E: PAIS SRM Organizational Chart (FY19)…………………………………………...….46

Appendix F: PAIS STSR Current and Future Funding……………………………………………...47

Appendix G: STSSN Roles and Responsibilities…………………………………………………….48

Appendix H: Corrective Action Plan - PAIS Beach Travel………………………………………….52

Appendix I: Interview Questions……………………………………………………………………..54

Appendix J: Superintendent E-mail…………………………………………………………………..57

Appendix K: NMFS E-mail…………………………………………………………………………….58

6

Figure 1. Map of Padre Island National Seashore.

7

1. Program Review Purpose, Scope, and Objectives

Prior to his retirement in fall 2019, the former Superintendent, Padre Island National Seashore

(PAIS or park), requested a review of the park’s sea turtle science and recovery (STSR)

program. This request was based on several factors: the Management Review completed in

July 2018 for PAIS and Palo Alto National Battlefield called for a more in-depth review of the

STSR program; the Superintendent was preparing to address a future funding shortfall for the

program and for staff succession planning; the STSR program had not been reviewed in its 40-

year existence (other than for safety and internal controls); and, the program review would be a

valuable resource for the new incoming Superintendent.

The scope of the review includes functional areas and operations of the STSR program. Five

objectives were established:

1. Identify appropriate mission functions of the program, including the role of

science/research.

2. Evaluate program staffing and identify positions and functions necessary to meet

mission requirements.

3. Evaluate program funding and determine financial resources required to meet mission

functions.

4. Evaluate interagency relationships and determine appropriate roles/responsibilities for

shared resource stewardship.

5. Document program successes and highlight practices that should be continued and

shared.

2. Assessment Methods

The program review consisted of three parts: 1) evaluation of plans and documents, 2) personal

interviews with all permanent STSR staff (two were interviewed by phone) and all members of

the park management team conducted on December 12, 2019, and 3) phone interviews with

other Federal and State agencies and partner organizations conducted during January-February

2020. Information from these sources was incorporated into the findings, discussion, and

recommendations included in section 4.

3. Program History and Context

PAIS was established in 1962, primarily for recreational purposes. The park’s Foundation

document (NPS, 2016), articulates the park’s purpose, significance, fundamental resources and

values (see Appendix A). The PAIS STSR program has a long history of success, having been

established more than 40 years ago in 1978 to aid in the recovery of the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle

(hereafter referred to as “Kemp’s”). The Kemp’s was listed as endangered in 1970, under the

Endangered Species Conservation Act, and subsequently listed endangered under the

Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (ESA or Act) throughout its range in Mexico and

in the U.S. This species is co-managed by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA)- National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in the marine environment and the U.S.

8

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in the terrestrial (coastal) environment. Primary threats to

Kemp’s include: 1) bycatch in fishing gear, 2) harvest and destruction of eggs, and 3) ocean

pollution/marine debris.

Bycatch in Fishing Gear

The major ongoing threat to Kemp's is bycatch in fishing gear. Kemp’s are primarily caught

in shrimp trawls, but also in recreational fishing gear, gill nets, traps and pots, and dredges

in the Gulf of Mexico and northwest Atlantic.

Harvest of Eggs

Almost the entire Kemp’s population nests along the coast of the state of Tamaulipas,

Mexico on the Gulf coast of Mexico, just south of the U.S.-Mexico border. Historically, egg

collection was an extreme threat in this area, but since nesting beaches were afforded

protection in both Mexico and the United States, this threat no longer poses a major

concern.

Ocean Pollution/Marine Debris

Marine turtles may die after ingesting fishing line, balloons, or plastic bags, plastic pieces, or

other plastic debris which they can mistake for food. They may also become entangled in

marine debris, including discarded or lost fishing gear, and can be killed or seriously injured.

A Bi-National Recovery Plan for Kemp’s was completed in 2011 (NMFS, 2011) as a second

revision of the original 1984 Recovery Plan. Dr. Donna Shaver of the NPS was a member of

the Recovery Team. A recovery plan is a guidance document, not a regulatory document. The

ESA envisions a recovery plan as the central organizing tool for guiding the FWS/NMFS and

their partners in efforts to recover a species – it identifies the actions necessary to support

recovery of the species, and identifies goals and criteria by which to measure progress.

In 2015, FWS/NMFS completed a 5-year status review of Kemp’s which assessed whether

recovery/downlisting criteria included in the revised Recovery Plan (2011) were met or progress

was made, as well as assessing the current status of the species. It concluded that identified

downlisting and demographic criteria have not been met and endangered status was

maintained.

Kemp's nesting is essentially limited to the beaches of the western Gulf of Mexico, primarily in

Tamaulipas, Mexico. Nesting also occurs in Veracruz, MX and a few historical records exist for

Campeche, MX. In the U.S., nesting occurs primarily in Texas (especially PAIS), and

occasionally in Florida, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina (see Figure 2).

9

Figure 2. Distribution and relative abundance of Kemp’s ridley nesting. (NMFS/FWS, 2015).

Kemp’s Status at PAIS

In 1977 there were estimated to be around 200 Kemp’s nesting females left in the world (NPS et

al., 1978). A record low number of nests (702) was produced rangewide in 1985. The primary

nesting site, where 99% of the rangewide nesting occurs, is in Mexico. In 1978, a ten-year

interagency action plan was developed, which included a goal for establishing a Kemp’s nesting

colony at PAIS. The park has been actively working since the 1980s to establish and maintain a

satellite population at PAIS that could contribute to global recovery of the species.

During the 1980s, a period of accelerating species decline, eggs from the primary Kemp’s

nesting beach in Mexico were relocated to PAIS to establish a secondary nesting colony in

order to safeguard against species extinction. In 1980, the park also began coordinating the

Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN), eventually expanding to include all

species of sea turtles in Texas. The STSSN is a cooperative effort of federal, state, and private

partners working to document causes of morbidity and mortality in sea turtles to inform

conservation management and recovery. In the 1990s, the park continued to develop, test, and

implement techniques to protect nests, incubate eggs, and produce hatchlings for continued

recovery of Kemp’s.

10

In the 2000s, the park expanded their beach patrol operations, incubation capacity, and actively

pursued sea turtle research. In 2002, the park expanded its incubation facility and sea turtle

program offices, and eventually developed a separate laboratory. From 2005-2007 the park

conducted a study to evaluate the potential for impacts to in situ nests from predators, tidal

inundation, human tampering, and vehicle driving (Walker and Shaver, 2008). From 2008-2010

a study was conducted to evaluate techniques for the use of corrals to incubate Kemp’s eggs

(Walker and Shaver, 2011). Corrals are temporary enclosures constructed in suitable areas on

the beach using fencing, which mimic natural processes because they allow eggs to incubate on

the beach under natural conditions while protecting nests from poaching and predation.

More recently (2010-2019), sea turtle strandings (vast majority being greens) have increased

dramatically in the Gulf of Mexico, especially in Texas, and have become a larger part of the

program’s work. The park’s nest patrol and management operations also increased during this

period.

A record high number of Kemp’s nests were recorded in 2017 (24,586 in Mexico; and 353 in

Texas, of which 219 were recorded at PAIS). Currently, the number of Kemp’s nests

documented at PAIS is about 1% of the rangewide total (see Appendix B). Nesting dropped in

2018 and 2019, which is typical due to the reproduction biology of the species (females nest

approximately every 2-3 years). For the 10-year period 2010 and 2019, an average of 110

nests were recorded annually at PAIS. A large nest production year is expected in 2020.

Unique management challenges exist in Texas at PAIS, including year-round beach driving

along all 61 miles of beach (except for 4 ½ miles that are closed) and the fact that Kemp’s nest

during the day. These circumstances present challenges for sea turtle conservation (even in a

“protected” national park unit) that are not present in other coastal NPS units. The park’s

intensive sea turtle nest monitoring and management program has continued to be implemented

to allow unrestricted public beach driving with motor vehicles and in response to reported beach

inundation that may be associated with ongoing erosion and sea level rise.

4. Findings, Discussion, and Recommendations

a. Mission Functions

Before we discuss findings of the STSR program functions, it is important to review the

responsibilities of Federal agencies under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), since it

serves as a guiding principle for Kemp’s management actions in PAIS. First, we are

required to aid and participate in the recovery of listed species by using our authorities to

conserve (recover) listed species (ESA section 7(a)(1)). This is often referred to as the

“proactive mandate”. Specifically, we must utilize our authorities in furtherance of the

purposes of the Act by carrying out programs for the conservation of endangered and

threatened species. Secondly, we must ensure that our actions (or those under our

authority) do not jeopardize the continued existence of the listed species. This is sometimes

referred to as the “reactive mandate”. Specifically, under section 7(a)(2) of ESA each

Federal agency shall, in consultation with and with the assistance of the Secretary, insure

11

that any action authorized, funded, or carried out by such agency is not likely to jeopardize

the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species. Lastly, it is illegal to

“take” a Federally listed species (section 9 of ESA). “Take” is defined to harass, harm,

pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, etc. (section 3 of ESA). The

FWS/NMFS can authorize take that is incidental to actions that are funded, authorized, or

carried out by a Federal agency under this section of the Act in the section 7 consultation

process and intentional take with a section 10 permit as applicable.

In short, under the Act our responsibilities are to provide for both the continued survival and

the recovery of Federally listed species, essentially a two-prong mandate. Below we

discuss important aspects of sea turtle management at PAIS and how they might apply to

our responsibilities under ESA and NPS policy.

As stated previously, the FWS/NMFS identified three major threats to Kemp’s: bycatch in

fishing gear, harvest of eggs, and ocean pollution/marine debris. None of these threats

directly apply to PAIS operations or are within the discretion of park management.

However, as discussed above, legal mandates under ESA call for the NPS to utilize our

authorities to develop proactive programs to conserve (recover) listed species and ensure

our actions do not result in jeopardizing the continued existence (survival) of the species.

The park’s sea turtle program focuses on three primary components: nest monitoring and

management, stranding response, and research. The park’s sea turtle program was

originally designed with a single-species focus on Kemp’s ridley, driven by the 1978

interagency Kemp’s action plan; although the STSR program has evolved over the years to

include other sea turtle species listed under the ESA that are present in the park, namely

green and loggerhead sea turtles.

i. Nest Management

Findings and Discussion

Kemp’s ridley sea turtle

Sea turtles are found in all warm and temperate waters throughout the world and

undergo long migrations, some as far as 1,400 miles, between their feeding grounds

and the beaches where they nest. That said, 95% of worldwide Kemp’s ridley nesting

occurs in the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. The three main nesting beaches in

Tamaulipas are Rancho Nuevo, Tepehuajes, and Barra del Tordo. Nesting also occurs

in Veracruz, Mexico, and in Texas, but on a much smaller scale. Occasional nesting

has been documented in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and

Florida (Figure 2).

While there is some documentation that suggests occasional and limited nesting of

Kemp’s historically occurred at PAIS (likely opportunistic), there is nothing in the

12

scientific literature that suggests PAIS ever hosted robust or even sustainable

populations of Kemp’s.

1

The park has carried out a voluntary, intensively managed

program to proactively propagate Kemp's ridley sea turtles that originated from the

1978 interagency action plan.

In the 1970s and 80s, Kemp’s were considered at risk of extinction, and emergency

actions (including nest relocation, incubation, and head starting) were necessary to

address the dramatic population loss that was occurring elsewhere in the listed

population in Mexico. Included among these actions was the goal of establishing a

secondary nesting population at PAIS, per the 1978 interagency action plan, which has

been achieved. This action was successful in increasing the number of Kemp’s

hatchlings at PAIS during the 1990s and 2000s. Recent evidence (Frey et al., 2020)

demonstrates that offspring of PAIS nesting females are returning to the park; however,

the majority of nesters at PAIS are from wild stock. Whether this level of intensive

wildlife management is still necessary is a legitimate scientific question now that

Kemp’s numbers have increased from the low identified in the 1970s that prompted

intervention.

In addition to the ESA, NPS Management Policies (NPS, 2006) require NPS units to

protect rare, threatened, or endangered species (4.4.2) and also actively work to

recover and restore all species native to parks listed under the ESA (4.4.2.3). The NPS

was a member of the Kemp’s Recovery Team that developed the original action plan

(NPS et. al., 1978), which called for the establishment of a secondary nesting colony at

PAIS. This was achieved in the 1990s and continues to be a major conservation

success. The work conducted in the 1980s and 1990s demonstrates that PAIS can

serve an important role as an alternate nesting site for a segment of the population in

the event of a catastrophic population crash in Mexico. The relative contribution that

PAIS makes to Kemp’s nesting is about 1% of the total nests. The park continues to be

an active member of the Recovery Team and a contributor to sea turtle conservation

science. Rangewide population recovery actions are now guided by the 2011 Bi-

National Recovery Plan for Kemp’s (NMFS, 2011).

The practice of nearly 100% nest relocation (removal and relocation of, or incubation of,

eggs to produce hatchlings) at PAIS has been, and is, precedent setting for the NPS.

Generally, the collection of all eggs to eliminate potential mortality due to beach driving,

predation, or ocean inundation is inconsistent with NPS Management Policies (Chapter

1

On page 11 of the PEER letter it noted an internal contradiction and possible error concerning the

historic evidence of Kemp’s nesting at PAIS. Although it appears that that there is not a robust record of

evidence of historic Kemp’s nesting at PAIS; some planning documents refer to the park as a major

nesting site of the Atlantic Ridley Turtle (PAIS Natural Resources Management Plan, 1974), while others

indicate sporadic nesting (Action Plan, Restoration and Enhancement of Atlantic Ridley Turtle

Populations, 1978). Definitive, place-based evidence is available for the primary nesting beach in Mexico,

while the anecdotal information noted by PEER provides the basis for PAIS. The 1978 Action Plan

included the goal of establishing a secondary nesting colony of Kemp’s at PAIS.

13

4), which requires natural processes to occur uninhibited to the degree possible. These

actions, however, in the context of an endangered population and sea level rise, may

be warranted to allow for the persistence of a small nesting population of Kemp’s at

PAIS, if that is still deemed necessary for the overall success of the species as it was in

1978. In order to determine the future of sea turtle nesting and suitable habitat along

coastal areas within National Parks, the following questions need to be addressed:

• Is it appropriate or beneficial in the long-term to completely bypass the natural

nesting process for all sea turtles?

• What long-term impacts may be caused by eliminating environmental factors that

affect natural selection through the relocation and laboratory incubation of all

nests?

• As sea level rise increases and inundation pressures make beach nesting more

and more difficult, will nest relocation and laboratory incubation be the only way

for the species to persist? And, if so, is PAIS the most logical place to do that?

• Does an intensive nest detection program detract from focus on addressing other

environmental or human caused mortality that recent recovery plans and species

status documents have identified as far more substantial to Kemp’s recovery?

From a larger NPS perspective, other coastal parks focused on allowing natural nesting

may face increasing pressure to relocate eggs to avoid potential or perceived impacts

that could be caused by recreational activities, predation, and inundation due to rising

sea levels.

The 2011 Kemp’s Bi-National Recovery Plan does not commit an agency to any action

within the plan, nor are those actions identified mandatory in nature, rather it identifies

goals and voluntary measures as a road map to species recovery. The plan focuses on

the core population in Mexico and reducing threats to the species. PAIS is included as

a “lead” agency for a variety of actions related to protecting and managing nesting

beaches. The Recovery Plan on pages I-24 to 25 includes PAIS STSR beach patrolling

and sea turtle nesting protection activities, including incubation and rearing of young, as

well as their educational programs. Additionally, the plan addresses how the park

manages oil and gas exploration and development as related to protecting park

resources, especially Kemp’s (page I-27).

The Recovery Plan does not include the PAIS nesting colony or hatchling production as

part of the downlisting criteria (see Appendix B). Nesting beaches and individuals at

PAIS are included as part of the delisting criteria, which includes Mexico and the U.S.

The plan does not require or prescribe the continuation of egg incubation and hatchling

release at PAIS, rather it focuses on “hatchling production necessary to achieve

recovery goals.” The plan includes an action (#214) for PAIS to assist with the

development of a nesting beach management plan for the three primary Mexico nesting

beaches. Similarly, the NPS does not have a beach management plan for PAIS.

The program review found two ESA section 7 consultations and associated biological

opinions (BO) related to Kemp’s at PAIS, which were prepared for the park’s beach

14

driving environmental assessment and the proposed construction of cabins to house

beach patrollers (both in 2011). The review found no programmatic BO exists for the

park’s sea turtle program. The NPS holds a take permit issued by the FWS

(TE840727-2, valid 7/15/19-1/31/23) that authorizes annual take of five species of sea

turtles (Kemp’s: 450 animals and 45,000 eggs/hatchlings; green: 3,000 animals and

300,000 eggs/hatchlings; loggerhead: 68 animals and 6,750 eggs/hatchlings). Take is

permitted for authorized research and management activities identified in the permit

(such as tagging, removing and incubating eggs, releasing hatchlings, etc.). There is

no analysis, BO, or authorized incidental take for impacts from public beach driving in

the park. According to FWS Ecological Services Office staff who were interviewed, the

PAIS sea turtle program is considered part of the ESA baseline for the Kemp’s listed

population, due to the longevity of the park’s program, and has been used as a static

part of the analysis to assess the effects of and authorize take by other agencies and

project proponents. Therefore, FWS asserts that any changes to the park’s sea turtle

program would require consultation under section 7 of the ESA (Dawn Gardiner, FWS

Biologist, personal communication, Feb. 18, 2020). FWS staff in the local Corpus

Christi office stated that over 20 BOs (for other agencies’ projects) would need to be re-

evaluated if PAIS were to change their sea turtle management program.

Green sea turtle

The green sea turtle (hereafter referred to as “greens”) was listed as endangered in

1978 under the ESA and was later reclassified by NMFS/FWS (North Atlantic Distinct

Population Segment (DPS)) to threatened in 2016 (NOAA, 2015). Factors contributing

to the green’s decline worldwide is the commercial harvest for eggs and meat; disease;

loss or degradation of nesting habitat; disorientation of hatchlings by beachfront lighting;

nest predation by native and non-native predators; degradation of foraging habitat;

marine pollution and debris; watercraft strikes; and channel dredging and commercial

fishing operations.

Four regions support nesting concentrations of particular interest in the North Atlantic

DPS: Costa Rica, Mexico, Cuba, and the U.S. (Florida). By far the most important

nesting concentration for green turtles in this DPS is Costa Rica. In the U.S., more than

53,000 green sea turtle nests were documented in Florida in 2019 (see Table 2,

Appendix B). The Texas coast and PAIS beaches support a relatively small number of

green sea turtle nests - only 97 since 1979 (23 of these nests occurred in 2017).

Recent evidence shows that the green sea turtle population continues to rebound

(Valdivia et al., 2019).

The most recently revised recovery plan for the U.S. Atlantic population was published

in 1991 (NMFS and FWS, 1991). The revised recovery plan focuses on Florida and

actions primarily by State and Federal agencies in Florida. The plan does not require

any specific PAIS actions; however, the NPS is included as one of many “responsible

15

agencies” under action #35 as it is recommended to post educational and informational

signs on important nesting beaches, as appropriate.

Loggerhead sea turtle

The loggerhead sea turtle was listed by NMFS/FWS as a threatened species

throughout its worldwide range in 1978. Like other sea turtle species, identified major

threats to this species include bottom trawl, pelagic longline, demersal longline, and

demersal large mesh gillnet fisheries; legal and illegal harvest; vessel strikes; beach

armoring; beach erosion; marine debris ingestion; oil pollution; light pollution; and

predation by native and exotic species (NMFS and FWS, 2008). Since listing, its status

has been periodically reviewed several times, with the most recent status review

completed in 2009. Currently, a new 5-year review is underway to update the status

and biology of this DPS. In the U.S., loggerhead sea turtles nest predominantly in

Atlantic coastal states as well as Florida and Alabama in the Gulf of Mexico. Total

estimated nesting in the U.S. is approximately 68,000 to 90,000 nests per year. 80-

90% of all loggerhead nesting in the U.S. occurs in Florida. Only 70 nests have been

documented in Texas since 1979. PAIS is within the Northern Gulf of Mexico Recovery

Unit which is the western extent of the U.S. nesting range. There are no specific

demographic recovery criteria or measures for PAIS, or populations within Texas,

identified in the most recent recovery plan for this species.

In addition to all Kemp’s ridley nests, the park protects, collects, and incubates eggs

from all green and loggerhead sea turtles. Green and loggerhead sea turtle eggs

collected at PAIS, and those collected elsewhere along the Texas coast and sent to the

park, are incubated at the park and the hatchlings are released on park beaches.

There seems to be no conservation reason to maintain this practice, and no EA, BO, or

other directive exists to support this management action. The majority of organizations

interviewed suggested that this practice should stop.

Hawksbill and leatherback sea turtles

Two other species of listed sea turtles occur at PAIS: hawksbill and leatherback, both of

which are endangered. Hawksbill nest mostly in the Caribbean and occur in the U.S.

primarily in Florida and Puerto Rico. One hawksbill nest was recorded in Texas at PAIS

in 1998. Leatherbacks nest mostly in the Virgin Islands and southeast Florida. PAIS

recorded one leatherback nest in 2008.

Recommendations

• The STSR program should transition to a sea turtle management program that is

more aligned with the 2011 Kemp’s Bi-national Recovery Plan and current practices.

The program should establish a formal 5-year strategic plan, with the assistance of a

professional facilitator, that is developed with input from the park’s management team

16

and includes other sea turtle experts from within the NPS. The STSR strategic plan

should identify appropriate roles for NPS, NMFS and FWS with respect to endangered

species management and recovery (with input from these agencies and other partners).

The focus of the program should be constrained to Kemp’s ridley nest protection,

followed by efforts to save stranded adult Kemp’s and green sea turtles (and other turtle

species), given that these individuals are important contributors to reproduction and this

activity is part of the STSSN that NMFS currently funds.

o The collection, incubation, and release of green and loggerhead eggs

should eventually be discontinued. Requests for project funding for sea

turtle research and management should favor Kemp’s ridley at PAIS.

• The park should begin to implement and test alternate management strategies

that better align with NPS policy, NMFS and FWS recovery goals, and biological

resource management principles that consider the entire Gulf of Mexico turtle

populations. A phased pilot program is recommended, with section 7 consultation

under the ESA, as necessary, to test in situ nest management and increased use of

corrals. In situ nest management, the practice used at all other NPS units with nesting

turtles, is most consistent with NPS policies and would allow for natural nesting of

turtles: thereby, subjecting the species to the biotic and abiotic factors that shape

populations and allow for their long-term persistence. A phased strategy could include

implementing and evaluating different nest management techniques in different

stretches of the beach. Implementation of this phased strategy could include near-,

mid-, and long-term management objectives. It is recognized that a strategy of this

form would need to be highly managed (identification, marking, and protection of nests)

to avoid and minimize impacts from beach driving, and would likely require an EA to

comply with the National Environmental Policy Act.

Near-term (1-2 years):

• Implement refined safety protocols (see Appendix H).

• Engage in the upcoming 5-year species status review of Kemp’s.

• Identify park-specific “measure(s) of success” for nest detection and

relocation, incubation at the facility versus corrals, and hatchling production and

release.

• Focus the STSR program on Kemp’s management and evaluate the

appropriate scaling of beach patrol and other program operations. Consider the

following strategies:

o MM60-30: In down island areas that receive less beach driving,

reductions in nest relocation should be the desired condition, including in

situ nest protection where nests are marked, fenced, and traffic is

diverted around them; similar to typical sea turtle nest management

performed on beaches elsewhere in the country. Pilot nest management

actions should be identified and evaluated. If nests must be moved in

this area, preference should be given to relocation to corrals.

▪ Patrols on down island stretches should be reduced to five

days per week (e.g. Thursday through Monday), 8- or 10-hour

17

days, and one or two patrols per day (as was done in the past).

Patrols can focus on protecting nests from beach driving and

monitoring to assess the potential impacts of inundation and

predation.

o MM30-17.5: A more intensive strategy of nest protection via relocation of

all nests and eggs to corrals.

o MM17.5-0: Front country areas could include continued relocation of

eggs to the incubation facility. Continue to utilize volunteers to patrol

front country beach and focus reduced staff resources on down island

areas.

Mid-term (3-5 years):

• Implement and monitor pilot actions described above and evaluate

species response.

• With federal and other partners, evaluate the long-term availability of

suitable Kemp’s nesting habitat at PAIS (and elsewhere along the Texas coast)

(e.g. National Wildlife Refuges and South Padre Island).

• Engage the State (and other partners) in dialogue about beach driving

management alternatives that maximize beach access but offset the need for, and

intensity of, beach patrol and nest relocation/incubation.

• Develop a long-term nest management strategy / beach management

plan.

Long-term (5-10 years):

• Continue implementation of the above strategies and work with partners

on species recovery actions, including public education, and management

planning that may need to be adapted due to sea level rise and continued loss of

habitat.

• The park should develop a strategy that establishes goals and objectives for

managing the entire portfolio of natural and cultural resources in the park, including sea

turtles. The strategy should address the entire suite of habitats and species within the

park and identify short-term priorities.

• Integration of the sea turtle program within the resource management and

science division would allow the park Superintendent to ensure that all priority

ecosystem programs are addressed, modify the program as needed to implement

adaptive management, address emerging priorities and issues, prioritize and allocate

limited resources, and implement efficiencies by having staff work across programs

based on seasonality and workload.

ii. Strandings

Findings and Discussion

18

The park has been functioning as the Texas coordinator for the STSSN since 1980.

Activities include: maintaining a network of permitted responders, training responders,

coordinating response to stranding events, collecting and transferring live and injured

turtles to approved rehabilitation facilities, necropsy of dead turtles and recording

associated data, maintaining data and reporting to NMFS. Park staff report that over

the last 10 years there has been a significant increase in the number of sea turtle

strandings that occur in the Gulf of Mexico and, in particular, in Texas at PAIS. Sea

grass, kelp beds, and algae in the Laguna Madre (inside the park) are a food source for

juvenile greens, and thus when stranding events occur, the park can see large numbers

of greens. The park indicates that the demands of these duties far exceeds the

capacity they have internally, which NMFS financially supports.

Most of the strandings on the Texas coast occur in PAIS or nearby; consequently, park

stranding staff are directly involved in the response. However, it also appears that NPS

staff routinely respond and provide assistance outside of the park boundary, rather than

relying on other STSSN responders. To date, it appears that the NPS has carried a

disproportionate burden on behalf of other jurisdictions.

Texas appears to perform a large number of necropsies of stranded sea turtles. NMFS

reports that about 200 necropsies are conducted for the Gulf Coast of Florida in one

year versus 400 per annum for Texas.

2

NMFS indicated that the park is performing

more necropsies than is required for large cold-stun events, and that they have

communicated to park staff that a reduction (sub-sample) is appropriate.

3

Other

suggestions from NMFS included not completing the full stranding form, measurements,

or tagging each animal during mass stranding events.

4

The park should evaluate the

relative cost-benefit of the data collected from performing large numbers of necropsies

in their overall management of the species versus the time and staffing costs that take

away from other natural resource monitoring and management activities.

Recommendations

• Transition from the park’s current stranding response and management model to

more of a coordination role in the state of Texas. The park’s necropsy activities and

protocols should be reviewed with NMFS to ensure that they do not go beyond what is

necessary to meet NMFS’ monitoring and research objectives for the necropsy program

and can be justified in light of the extraordinary time and resources spent to maintain

that level of activity.

o Stranding response should be focused to inside the boundaries of PAIS and

partners and other agencies should respond to non-NPS locations. This

should be based on an assessment of NPS resources and capacity to carry

2

Correction made based on information provided by NMFS (see Appendix K).

3

Correction made based on information provided by NMFS (see Appendix K).

4

Correction made based on information provided by NMFS (see Appendix K).

19

out these activities. See section c. (Staffing) for additional recommendations

on stranding response.

o Submit a funding request proposal to NMFS for additional support for cold

stun response in 2021. Requests are due in August 2020 when the mid-year

STSSN report must be filed.

o Consult with NMFS on STSSN necropsy requirements and lab operations.

o The stranding coordinator is meant to be a facilitator of the response.

Response activities should be delegated to other volunteers and entities rather

than PAIS being solely responsible. If PAIS continues as stranding

coordinator, a more robust response network should be developed; NMFS

indicated they are willing to assist with this.

iii. Research

Findings and Discussion

The park has an active research program and staff have authored or co-authored

dozens of scientific publications over the last 20 years. Nearly all of the STSR

permanent staff members are actively engaged in manuscript production and

publishing. Conducting and facilitating research is among the primary goals of the

program, according to the park’s website. Park staff’s significant production of science

via peer reviewed publications represents an exceptional contribution to the state of

knowledge on sea turtle biology, ecology, and coastal biological resource management.

It is clear that PAIS has made substantial contributions to the overall body of research

and scientific knowledge of sea turtles. This review did not address whether the

research substantially contributed to, addressed, or guided park management actions

related to sea turtle management or other park activities at PAIS.

Recommendations

• Focus research towards efforts that directly improves management of the

species within the park.

• Any Kemp’s ridley research needs or projects should be closely coordinated with

the national Kemp’s Recovery Team and the defined needs of the recovery

plan/program. Sea turtle research that is focused on impacts, ecology, and other topics

outside the park, or of a more academic nature, may be supported but should be

carefully balanced with the costs and tradeoffs associated with an inability to monitor,

manage, and study the other myriad natural and cultural resources at PAIS.

• Contributing to scientific publications is appropriate and admirable, however,

publishing should not be a driver of STSR program or individual success. The park

should actively work with outside partners to identify and conduct future research that

has in the past been conducted by NPS staff.

• Research conducted in the park (whether by a cooperator or by NPS personnel)

should be analyzed and authorized through the issuance of a research permit and

20

tracked in the Research Permit Reporting System (RPRS). All requests for research in

the park should be evaluated by an interdisciplinary team and approved by the

Superintendent.

• When considering and refining what additional science and research is needed to

address park management issues, the park should consider developing a natural

resource science plan or prospectus. The plan would need to identify management

goals and targets and key uncertainties that would benefit from potential research

projects. Those research projects should then be prioritized and conducted in a

manner so that the results would directly inform key management questions and assist

with adaptive management. Preliminary areas of study may include:

o Climate change modeling/scenario planning to evaluate impacts to sea turtle

nesting habitat and to investigate alternative nesting sites.

o Beach erosion and accretion studies to evaluate and model future sea turtle

nesting habitat.

• To assist in prioritizing and focusing future research related to sea turtles, the

park could request a cooperator to conduct a literature search to develop a summary of

the program’s research that focuses on the extent to which PAIS STSR-funded

research and publications have: a) provided information applicable to park

management, b) leveraged existing work of other researchers, c) been utilized by other

authors, and d) fostered international collaboration.

• Ensure research follows NPS and Department of the Interior (DOI) policies,

including: NPS Director’s Order 79: Integrity of Scientific and Scholarly Activities; DOI

Scientific Integrity Policy; and DOI Scientific Integrity Procedures Handbook.

b. Funding

Based on current operational activities and organizational structure, PAIS leadership and

staff in and outside of the sea turtle program have identified potential future funding

shortfalls as early as 2025 and should be commended for their foresight in identifying the

issue. In the next 3-5 years, the STSR program may be unable to support current

operations and discretionary activities considering workloads of existing staff and the current

staffing organization. Since inception, the turtle program has and continues to rely on

several short-term funding streams (e.g. Natural Resource project funding, donations, and

several varied short-term funding projects related to the Deepwater Horizon Natural

Resource Damage Assessment settlement). Current ONPS funds that PAIS directly

controls for daily operations are insufficient, given the existing activities and programs of the

STSR division. Several areas of support or subsidy continue to be provided to the STSR

program from umbrella Parkwide ONPS allocations and are not tracked, accounted, or are

only partially incorporated into budget and planning of the STSR program (e.g. the Facilities

Management employee dedicated for about half the year to repair and maintain the large

fleet of traditional and UTV vehicles). The sea turtle program also assumes several

activities well outside of park boundaries and the park’s primary responsibility. Interviews

with representatives from FWS and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) indicate

that neither the FWS nor the State of Texas provide funding support to the PAIS STSR

21

program (though Texas has provided substantial support, in-kind, boats and other

equipment, during stranding events). Without additional funding the park still conducts sea

turtle management and recovery activities (e.g. collection of turtle eggs, hatching and

release) which serve as mitigation measures that are presumably related to BOs issued by

the FWS for projects along the entire Texas coast and well beyond the boundaries and

administrative responsibilities of PAIS and the NPS.

Several areas of business and program risk have been identified, including some identified

as early as April 2016, that are largely unaddressed, most notably overtime well outside of

Bureau policy and authority.

Key Issues

There are many issues related to funding that surfaced during the PAIS STSR program

review and many of them are intertwined or overlap with other issues that are addressed in

other sections of this report. Consequently, the review team chose to focus on the following

three issues because a.) they rose to the top in terms of impacts (both direct and indirect

and short term/long term), and b.) were broad enough to allow other important issues to

logically nest under them.

i. Overtime and other staffing costs.

ii. Short-term project funding was used to create long-term funding obligations.

iii. The funding level of the STSR program is not aligned with overall park priorities.

i. Overtime and other staffing costs

Findings and Discussion

Following an April 2016 Internal Controls Audit of several PAIS programs and operations,

the audit team noted that the STSR program paid $162,320.10 in overtime for FY2015

and had seven employees that exceeded 250 hours of overtime, including two that

exceeded 600 hours. NPS policy requires that “Bureau heads must approve overtime

pay for non-emergency situations involving: … Overtime pay in excess of 600 hours in a

fiscal year for an employee at any grade level.” (Personnel Management Letter (PML) No.

88-5, May 16, 1988). The supplemental report on overtime also indicated that alternative

forms of overtime (e.g. compensatory time) also need be accounted for as if they were

overtime in any bi-weekly pay limitations. In FY2016 when the internal audit and

recommendations were developed, the turtle program recorded a total of $127,580 of

overtime and that amount has increased every year to a FY2019 total of $201,232 of

regular overtime for 44 employees and Administratively Uncontrollable Overtime (AUO)

for two employees. The number of employees that worked over 250 hours of overtime

has not decreased. In FY2016, seven employees had over 250 hours overtime. In

FY2019, 27 employees had between 100 and 249 hours of overtime, eight employees

had between 250 and 399 hours of overtime, and two employees recorded 433 hours and

569 hours, respectively.

22

Approximately 7,845 hours of regular overtime were recorded in FY19. Based on the

overtime pattern that has occurred for at least five years, the work attributed to these

hours is assumed to be a critical need and should be addressed by additional personnel,

rather than significant amounts of overtime being incurred over a long period of time.

This represents approximately seven seasonals (at 1040 hours/season) or

10 seasonals (for the nesting season of 720 hours). If additional staff were hired to cover

the above hours, total costs would be less than what was paid out of overtime since these

staff would presumably be accomplishing the hours of extra work deemed critical at

standard pay rates.

In FY2019, $35,978 was paid out as AUO. This amount is equivalent to two GS-5 6-

month seasonals ($18,889/season or $37,778) or three GS-4 nesting season seasonals

($10,857/season or $32,571).

Overall, in FY2019, $201,232 was paid out in overtime and AUO (14.6% of the STSR

base budget). This represents nearly 19 additional GS-4 seasonals ($10,858/ 720-hour

seasonal) or 11 additional GS-5 six-month seasonals ($18,889/1040-hour seasonal).

Prior to obtaining a minimum 332% increase in ONPS funds between FY2008 and

FY2019 ($413,850 ONPS in FY2008 to $1,443,000 in FY2010 to $1,374,902 in FY2019),

the STSR program consisted of two permanents and two GS-5 term employees and 24

GS-4 seasonal employees (with four seasonal employees identified as vacant) in

FY2008. By 2019, the program had one GS-13 permanent-full-time (PFT), one GS-11

PFT, three GS-7 PFT, one GS-6 PFT, one GS-7 permanent career seasonal (PCS), one

GS-5 PCS, and as many as 35 to 41 seasonals. In addition, five PFT and PCS positions

were listed as vacant but are included in the latest signed organization chart (Appendix

C). Statements from park staff have indicated a need to hire more staff to assist in

accomplishing program activities, as developed by the Division Chief and approved by

the Superintendent.

The current fixed cost commitment of seven permanent employees is $482,901. Two

additional permanent employees (one GS-7 PFT and one GS-5 PCS) are paid out

of NOAA Restoration Stranding funds (currently funded at $112,000/year) and currently

cost $104,286. In FY2019, approximately 35 seasonals worked for the program with 29

working primarily around the nesting season (April through mid-July

equating approximately 640-720 hours) and six employees working about the full six

months (1040 hours). The seasonal costs during the nesting season were estimated

at $314,770 and the 6-month seasonal costs were estimated at $113,334. Total

personnel services for a year (not including STSSN permanent salaries) are estimated

at $912,105 with the above personnel configuration. This figure represents

approximately 66% of the current allocated ONPS base funds. Total personnel services

costs would be $1,016,391 or 74% of the current base allocation when the two

23

permanent personnel, currently working on STSSN project funds, are included in

personnel services costs.

Recommendations

The 2016 overtime audit recommended 11 different actions for the park and program to

undertake. Specifically, the audit recommended: “After discussion with park

management and regional staff, a cohesive effort in regard to overtime should be made to

consider employee well-being, employee safety, staff morale, ensuring all mandated laws

and NPS policies are followed, and ensure the park establishes effective controls over

overtime and premium pay.” To date, we are only aware of one recommendation, AUO,

that was pursued. Specific recommendations from the 2016 report are included

and are again recommended:

• “(a) Reassigning work to other employees,

• (b) Rescheduling tours of duty,

• (c) Using flexible and compressed work schedules,

• (d) Establishing work priorities,

• (e) Discontinuing low priority activities, and

• (f) Seeking other more cost-effective alternatives.”

Other recommendations include:

• Supervisors should pre-schedule, and per NPS and other policies, supervisors

must pre-approve all overtime deemed essential to carry out critical program activities.

o Unless an actual emergency response is required (e.g. human health and

safety), personnel should not be allowed or authorized to work overtime (including

compensatory time) without prior written or documented approval. Overtime

requests should clearly state the nature and justification for the overtime.

• The Division Chief should develop a staffing plan and prioritize work to

immediately reduce all overtime to 1.2% of the turtle program’s ONPS base allocation

(based on NPS Scorecard standards).

o Based on a FY2019 ONPS Base allocation of $1,374,902, overtime should not

exceed approximately $16,500.

o Stand-by pay and AUO should not be authorized.

o In three years, an objective should be that overtime and compensatory time

are only used for short-term emergency response activities.

• Hire additional seasonal staff and implement shift tour of duties, reassign and

redistribute work responsibilities to other staff, with particular emphasis to address those

critical duties and critical times where nighttime work is essential for Kemp’s egg care.

o Other more cost-effective administrative solutions and staffing solutions are

available and should be fully explored and implemented. In the case of AUO, in

addition to other considerations, these administrative options must be explored

before implementing AUO…“In such a situation, the hours of duty cannot be

controlled by such administrative devices as hiring additional personnel;

rescheduling the hours of duty (which can be done when, for example, a type of

24

work occurs primarily at certain times of the day); or granting compensatory time

off duty to offset overtime hours required.” (5 CFR, Ch 1§550.153).

ii. Short-term project funding was used to create long-term funding obligations.

Findings and Discussion

The park has been very successful in obtaining project funding to maintain and grow its

nest detection and patrol program (over $14M in project funds since 1994). Funding from

several internal NPS sources [USGS-Natural Resource Preservation Program (USGS-

NRPP), Natural Resource Fund Source (NRFS), and Southwest Border Resource

Protection Program (SWBRPP)] have been used to fund STSR operations and have

enabled the expansion of the program. Unlike “programs”, projects are typically defined

as “a temporary undertaking to create a unique product or service.” A project has a

defined start and endpoint and specific objectives that, when attained, signify completion.

PMIS records show that the STSR program has been receiving these project funds

annually for nearly 20 years; often with small changes to project scope and title.

From 2019 through 2026, total projected funding allocated to the sea turtle program

averages approximately $1,996,000/year. Total projected annual soft (project) funding

from 2019 through 2026 averages about $621,000/year with approximately

$519,900/year coming from Deepwater Horizon (DWH) restoration related funding. One-

time event soft funds, in this case DWH funds, currently comprise an annual average

of 26% of the program. Other competitive NPS funds over the 8-year period average

approximately 5% of the program.

Beginning in FY2017, NMFS has been providing approximately $112,000 to support the

STSR program in carrying out duties related to serving as the Texas state coordinator of

the STSSN.

5

Beginning in FY2018, the park also started receiving approximately

$139,000 in stranding support funds from the DOI Deepwater Horizon Trust Fund.

Despite nearly $250,000/year in project fund support for stranding activities, the park

indicates that response needs exceed available funds. NMFS staff indicated that when

the Texas STSSN mid-year report (for the period Jan.-June) is due in August 2020,

additional funds could be requested for the next fiscal year.

6

While the park does not track individual fuel usage by program or division, interviews

indicated that possibly as much as half of the parkwide fuel used in a season might be

5

The DWH Sea Turtle Early Restoration Project provides support to each of the state stranding networks

in the Gulf of Mexico annually. These funds are explicitly intended for enhancement of the five state

stranding networks in order to achieve restoration benefits. See Appendix K.

6

These proposals must be for stranding network enhancement projects. The DWH Sea Turtle Early

Restoration Project funds are explicitly intended for enhancement of the STSSN in order to achieve

restoration benefits. To date, PAIS has received an additional $129,000 (2018-2019) for two seasonal

stranding response positions at Packery Channel, two SCA interns for stranding response, and necropsy

facility improvements. See Appendix K.

25

attributed to the STSR program. The turtle program reported patrolling 229,220 km

(142,431 mi), 234,787 km (145,890 mi) and 251,022 km (155,978 mi) of beach during the

turtle nesting season from 2016 through 2018, respectively. An analysis of fuel usage for

nest patrol activities was completed using an estimate of 10 miles per gallon for all

vehicles, which results in fuel costs of about $32,000/year.

Recommendations

• Ensure that ongoing STSR program operations (recurring, permanent work) is

funded by park base (or other reliable and dedicated funding) and not by special project

funding that is meant to fund specific projects. Project funds should not be used to fund

permanent personnel (except for Career Seasonal employees during their non-core

season), activities, or purchases that create ongoing or future costs/obligations of any

kind.

o Requests for project funding for sea turtle research and management should

favor Kemp’s ridley at PAIS. PMIS#248312, which focuses on night-time

protection and collection of green sea turtle eggs (FY21-23), should be cancelled

and WASO notified. Similarly, SWBRPP funds should not be awarded to and

used by PAIS for ongoing research and management activities for green sea

turtles (PMIS#305534 for FY21). Projects must not support continuation of

existing or operational activities and recurrent monitoring and surveys.

• The park should begin planning for what critical activities must be accomplished

with a 30% reduction in funding resources available.

o One-time event or recovery funding like DWH should not be used to build

programs. Restoration funding like DWH is intended to recover from damages

caused by disasters (or provide for compensatory restoration) to a baseline that

existed prior to the event. This funding expires in 2025, and the park should

have no expectation other funds will become available to fill this perceived

shortfall.

• Personnel services costs for this program should not exceed about 80% of the

ONPS base allocations (based on NPS best practice and Budget Office guidance).

o Annual position management should be discussed with the Superintendent,

particularly when any permanent position becomes vacant. Replacing a vacant

position in-kind should not be assumed.

o Seasonal staffing strategies should be developed to reduce overtime needs that

reflect 1.2% of ONPS base funding.

o New staffing configurations must be developed along with scaling back currently

configured patrol efforts to stay within current ONPS allocations and reduce the

reliance on additional parkwide ONPS funding and unreliable soft funding sources.

o Two staffing plans should be developed with the above constraints,

a minimal staffing plan emphasizing minimal and critical work requirements

and an optimal or desired staffing plan (that includes discretionary activities).

• Develop STSR annual work plans that specify tasks, budget and staffing that are

approved by the Superintendent and monitored and tracked regularly. Ideally this would

26

incorporate measures to document and verify that expenditures (including staff time) are

made consistent with fund source purposes and requirements.

• All capital expenditures over $10,000 should be approved by the Superintendent,

after budget forecasting analysis has been completed by the Division Chief.

• Generate philanthropic support. There are abundant opportunities for the STSR

program to leverage the high public support for sea turtle protection. The sea turtle

program at PAIS is well regarded and the species are charismatic and generally beloved

by the American public. The park could work with partners to develop a "friends group" or

philanthropic support organization that could raise funds for priority sea turtle

management and research. Similarly, many non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

have existing and well-funded programs that support sea turtle conservation worldwide

that the park could tap into by establishing new relationships. Additionally, a significant

amount of public environmental education may be accomplished through a philanthropic

support work plan that would be implemented by a friends group.

• Implement a pilot user fee for cost recovery. The park may consider a permit

program to recover costs associated with implementation of the unrestricted off-road

vehicle (ORV) program. A permit program could generate substantial cost recovery

associated with the needs to protect sea turtles and other wildlife species while allowing

for recreational beach driving. Other NPS units, such as Cape Cod National Seashore,

Cape Hatteras National Seashore, and Assateague Island National Seashore, implement

cost recovery permit programs for implementation of their ORV and protected species

management programs. These programs can generate revenue to offset costs

associated with management activities that are conducted to allow the ORV use. Cost

recovery permit programs are a widely used practice throughout the NPS system.

o A reasonable approach would be to require a beach vehicle driving permit for the

period April 1-July 15, which is the Kemp’s nesting season, when potential

impacts to nesting turtles and eggs could occur. Fees collected should be

commensurate with the cost of the NPS operating the mitigation program.

• Program personnel should stop conducting management activities that occur

outside PAIS boundaries and evaluate elimination of some duties that take park staff

away from higher priority activities in PAIS.

o Documents and interviews with staff and other agencies indicate STSR

personnel are conducting field activities (e.g. turtle stranding recovery, egg

collection, beach surveys, etc.) outside PAIS boundaries. This is a liability

concern for the NPS. Other agencies or groups should assume these duties or

activities outside PAIS boundaries. If others (for example, FWS, TPWD,

NMFS) cannot or do not assume these activities then this would indicate a lower

priority to those groups and thus not relevant to PAIS priorities.

• Other fixed costs should be identified and included in the STSR program budget.

o Itemize and incorporate line item budgets for actual high capital equipment

costs and repairs (e.g. vehicles, UTVs, etc.), fixed fuel costs (at least

$30,000/year), building utility and maintenance costs, anticipated other supplies

and equipment costs and support costs needed for other Divisions, such as when

public releases are planned.

27

o The STSR program should immediately begin building in and accounting for fuel

costs, not only for nest patrol, but for other important programs like the STSSN

program. For the near term a figure of $30,000/year can be used for FY20 and

FY21, which is consistent with a line item identified in the park’s original OFS

budget increase request to the Regional Director for approximately $1.2 million

for the turtle program.

o Install a fuel metering system to track fuel usage by vehicle and/or Division. This

will allow all Divisions and the park to plan for future fixed costs. Electronic fuel

metering is a best practice for all parks.

• The current personnel and position configuration for the STSSN coordination

program should remain as is until 2025 and incorporate those personnel services from

that program into the STSR ONPS base by FY2026.

o Nearly six years of outside funding is available to support the STSSN activities,

which is sufficient time to recalibrate work efforts to operate within the provided

funding level and to further develop the network, contacts, procedures, training

program, and cadre of outside entities needed for responding to strandings outside

the park. If after 2025, PAIS chooses to maintain the Texas STSSN

coordination role, the program and duties should be scaled back to focus

and emphasize coordination, training, and reporting; and with limited use of ONPS

funds.

o The STSSN funds ($112,000) that NMFS provides currently pay for these

personnel and they should be allowed to only focus on the many duties the STSSN

requires for in-park strandings (see Appendix G, section on State Stranding

Coordinators and Stranding Responders). If these personnel are occasionally

needed for other critical duties, then NMFS should be consulted and other funding

allocated for that work, particularly for the Career Seasonal employee.

7

o After 2025, the one permanent full time and one permanent career seasonal total

salary of $104,286 (FY2019) will need to be incorporated into ONPS base funds,

should PAIS choose to remain as the Texas Coordinator.

o By FY2021, the park should begin working with other partners (e.g. FWS,

volunteer groups, etc.) so that other partners are responsible for and patrol the

beach outside of PAIS boundaries, particularly during the Kemp’s nesting season

(see Appendix G, Stranding Responders).

• The park management team should discuss how they want to address significant

support (staffing or monetary) provided by other divisions for turtle program operations,

including turtle release events.

o The number of public hatchling release events is a discretionary activity

and should be reduced. Total actual costs of these events (all personnel and

time) should be tallied in FY20 so the Division Chief and Park Superintendent can

7

Personnel supported with DWH Sea Turtle Early Restoration Project funds are intended to support the

TX STSSN as a whole in order to enhance the network effectiveness across the state (e.g., additional

training, statewide data entry/data management, necropsy support). If these personnel work on other park

projects/activities then their time spent on those activities must be paid with other funding sources. See

Appendix K.

28

identify how many public events can be planned in relation to budget availability to

support these events and other park priorities and needs. Another possibility

would be to identify one week of the year where turtle releases and related public

events would occur (“Turtle Week!” or “Turtle Daze!”), thereby allowing staff to

effectively plan for and conduct outreach and education activities.

iii. The funding level of the STSR program is not aligned with overall park

priorities.

Findings and Discussion

The park's current (FY20) budget for the sea turtle program is $2,196,055 (see Appendix

F). The sea turtle program’s annual base funding (ONPS) is $1,374,902. As such, the

STSR base budget is equal to nearly one quarter (23.8%) of the park’s ONPS budget. In

addition, the program typically secures between $500,000 - $1,000,000 in project funds

each year.

The Science and Resources Management (SRM) division’s budget ($248,670 in FY20),

which is used to manage all other natural and cultural resources science and

stewardship, planning and compliance, and Native American relations, is only 4.3% of the

park’s base budget. The Regional average of park base budget for resource

management programs (which includes cultural and natural resources) was 12.5% in

2018. The STSR percent of park base is about twice the Regional average. Conversely,

the SRM program is funded at a small fraction of the regional average. The park’s

Scorecard shows zero staff, zero labor spending, and zero base funds being applied to

cultural resource stewardship responsibilities, and no use of volunteers in the program

(NPS, 2019). The perception of some park staff is that most natural and cultural resource

management programs have been largely ignored as a result of the intense and

disproportionately high allocation of financial and staff resources applied to the sea turtle

program.

The park’s Foundation document includes a variety of other park resources and values

that warrant study, management, and protection, including nine other listed species. The

resources (funding and staffing) available for protecting, restoring and interpreting those

other resources is much less than the funding levels for the STSR program and in some

cases completely non-existent.

The park has many important and internationally significant natural and cultural resources

that are not being monitored, studied, or managed. For example, the park provides

habitat for more than 300 bird species, it contains 16th century Spanish shipwrecks, and

there are thousands of acres of prairie, dune habitat, and freshwater marshes. The

Laguna Madre within PAIS is considered one of only about 6 hyper-saline lagoons in the

world, where close to 80% of all redhead ducks winter in the U.S., about 80% of all

seagrass beds occur in the entire state of Texas, and where Federally- and State-listed

29

migratory bird species find important habitat. The park’s natural resource condition

assessment documents that a majority of ecological communities and resources in the

park have insufficient information to establish their current condition and trend (Amberg

et. al., 2014). These unique and sensitive resources may be threatened by visitor, and

adjacent land uses.